Liens de la barre de menu commune

Liens institutionnels

-

Bureau de la traduction

Portail linguistique du Canada

-

TERMIUM Plus®

-

Auteurs

- + Auverana, Iliana

- + Barber, Katherine

- + Blais, François

- + Boileau, Monique

- + Bucens, Vic

- + Cloutier, Yvan

- + Cole, Wayne

- + Collier, Linda P.

- + Collishaw, Barbara

- + Cormier, Chantal

- + Delisle, Jean

- + Doumbia, Bréhima

- + Ethier, Sheila

- + Fitzgerald, Heather

- + Gariépy, Julie L.

- + Gawn, Peter

- + Ghearáin, Helena Ní

- + Guyon, André

- + Harries, Emma

- + Hug, Christine

- + Joe, Gregg

- + Jope, James

- + Lacroix, Kim

- + Laforge, Marc

- + Landry, Alain

- + Lapointe, Lucie

- + Lawrence, C.A.

- + Leighton, Heather

- + Lemieux, Claude

- + Leroux, Paul

- + Matsune, Heather

- + McClintock, Barbara

- + McNamer, Patrick

- + Mossop, Brian

- + Oslund, Richard

- + Ouimet, Nicole

- + Peck, Frances

- + Pontisso, Robert

- + Racicot, André

- + Roberts, David

- + Rodríguez, Nadia

- + Ross, Sheila M.

- + Roumer, Camilo

- - Samson, Emmanuelle

- + Sanders, Sheila

- + Schnell, Bettina

- + Senécal, André

- + Shatalov, Dmitry

- + Siemienska-Vachali, Maja

- + Sitarski, Mary

- + Skeete, Charles

- + Taravella, AnneMarie

- + Tautu, Doris

- + Urdininea, Frances

- + Vittecoq, Fanny

- + Wellington, Me Louise Maguire

Divulgation proactive

Avis important

La présente version de l'outil Favourite Articles a été archivée et ne sera plus mise à jour jusqu'à son retrait définitif.

Veuillez consulter la version remaniée de l'outil Favourite Articles pour obtenir notre contenu le plus à jour, et n'oubliez pas de modifier vos favoris!

La zone de recherche et les fonctionnalités

Clear and effective communication for better retention of information

When you write, you transmit information on a topic that you know well. You are in familiar territory; the information is part of a body of knowledge stored in your memory. For the reader, however, this is new information. If you do not present the information in a way that makes it easy to retain, your reader may not remember much of it, or indeed remember having read it.

To help readers easily retain the information you present to them, it is worthwhile knowing how your readers process information and store it in their memories.

Information processing

What exactly happens in the readers’ brains when they read a text? First of all, the information enters their short-term memories, also known as working memories. The information is stored in this memory for about 30 seconds. Then two things are possible: the readers either forget the information or transfer it to their long-term memories.

Information retention

As a writer, you need to ensure that the largest possible amount of information goes from your readers’ short-term memories to their long-term memories. To do that, you have to look at the number of items of information you are providing, the order in which you present them and your readers’ degree of familiarity with the information.

Number of items

According to the psychologist George A. Miller, human beings can store between five and nine blocks of information in their short-term memories. This is what Miller called the "magic number of 7 ± 2."

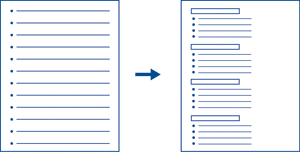

Let’s look at an example. The text you have written contains a series of 12 items in a bulleted list. In this type of list, each bullet corresponds to a block of information. After reading the 12 items in the bulleted list, your reader will usually retain a maximum of 9 items in the list because the short-term memory can only retain between 5 and 9 blocks of information.

Could your readers retain more items of information? According to Miller’s research, readers can push back the boundaries of their short-term memories when they are able to establish links between certain items of information and recode them in their brains by placing them in categories.

Let’s go back to the previous example. To ensure that your readers retain more information, you could divide your bulleted list of 12 items into several categories by grouping the items that go together and giving each category a catchy title. Thus, each category, which now contains several bullets, will be perceived as a single block of information. This will enable readers to retain a maximum of 9 categories rather than a maximum of 9 bulleted items.

The associative work that you did will help your readers to increase the capacity of their short-term memories and assimilate a greater amount of information.

Order of items

Once your readers have read all of the items presented in each category, they will retain some of the items more easily than others. In fact, the first items will be more likely to pass from the readers’ short-term memories to their long-term memories.

This phenomenon is clearly demonstrated in a study done by researchers Glanzer and Cunitz. The participants in their study had to first read a list of words, then carry out an arithmetic task for 30 seconds. This task was intended to distract their attention from the list. When the researchers asked them to list the words they had retained, they were able to remember only the first items on the list.

Why did they retain only the first items? When the first items entered the readers’ short-term memories, the memories had enough space to carry out the transfer to the long-term memory using an automatic recall mechanism. Items in the middle and at the end of the list usually stayed in the short-term memory and quickly disappeared when the readers did another task.

Degree of familiarity

If readers are already familiar with the information presented, they will find it easier to transmit it from their short-term memories to their long-term memories. For example, if your readers are more familiar with the imperial system than with the metric system, they will more easily retain the information that a person is 5 feet, 6 inches tall rather than 1.70 metres tall.

Also, your readers will more easily assimilate new information that you present to them if you associate it with knowledge that they already have. Your readers can therefore use what they already know to understand and retain the new information.

If you take into account the method the brain uses to process information and you apply techniques that encourage the retention of information, your written message will be more effective. And readers who have thoroughly assimilated important information can make better use of it.

Sources

GLANZER, M. and CUNITZ, A. "Two Storage Mechanisms in Free Recall", Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, Vol. 5, No. 4 (August 1966), pp. 351-360.

MILLER, George A. "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information", Psychological Review, Vol. 63, No. 2 (March 1956), pp. 81-97.

© Services publics et Approvisionnement Canada, 2025

TERMIUM Plus®, la banque de données terminologiques et linguistiques du gouvernement du Canada

Outils d'aide à la rédaction – Favourite Articles

Un produit du Bureau de la traduction