Liens de la barre de menu commune

Liens institutionnels

-

Bureau de la traduction

Portail linguistique du Canada

-

TERMIUM Plus®

-

Titres

- Aboriginal Titles

- Adjective/Adverb Aptitude

- A Look at Terminology Adapted to the Requirements of Interpretation

- Alphabet soup

- A Passion for Our Profession

- Apostroph-Ease

- A Procedure for Self-Revision

- A Question of Sound, not Sight

- Are You Begging the Question?

- Are you concerned about data security?

- Assessing translation memory functionalities

- A trilingual parliamentary glossary

- Baudelaire translated in prison by a translation professor

- Big bang and gazing into the twitterverse

- Bill Gates Protecting the Spanish Language?

- Boost Your eQ (E-mail Intelligence)

- Brave New World: Globalization, Internationalization and Localization

- Bridging the Gap

- Canada’s jurilinguistic centres

- Canadian Bijuralism: Harmonization Issues

- Cancelling Commas: Unnecessary Commas

- Changing Methodologies: A Journey Through Time

- Character Sets and Their Mysteries. . .

- Clear and effective communication for better retention of information

- Clear and effective communication: Make your readers’ task easier

- Clear and Effective Communication: Reducing the Level of Inference

- Closing in and trailing off: More digressions in punctuation

- Cloud computing

- Comashes and interro-what’s‽: Digressions in punctuation

- Commas Count: Necessary Commas

- Conference Interpretation: A Small Section with a Big Mission

- Controlling Emphasis: Coordination and Subordination

- Coping with Quotation Marks

- Corpus use and translating

- Don’t throw in the towel!

- Dubious Agreement (Part I)

- Dubious Agreement (Part II)

- Email: At once a blessing and a curse

- Emergence of New Bijural Terminology in Federal Legislation

- English Then and Now

- English Usage Guides (1974, vol. 7, 4)

- English Usage Guides (1974, vol. 7, 5)

- English Usage Guides (1974, vol. 7, 6)

- Evaluating Interpreters at Work — or Trying Not to Feel Superfluous

- Excuse Me, Have You Misplaced Your Modifier?

- FAQs on Writing the Date

- FAQs on Writing the Time of Day

- Fifty Years of Parliamentary Interpretation

- Flotsam and Jetsam of Question Period

- Forty Years of Development in the Blink of an Eye

- From book crossing to wikis

- From brand names to the smart grid

- From catchphrases to unfriend

- From Ocean to Ocean: Names of Undersea Features in the Area of the Titanic Wreck

- Further questions from the inbox

- Gender-neutral writing (Part 1): The pronoun problem

- Gender-neutral writing (Part 2): Questions of usage

- Getting to the point with bullets

- Globalization and the Forgotten Language Professionals

- Grammar Myths

- Green Buildings: Passive Solar Design

- High-Tech Translation in the Information Age

- How English has been shaped by French and other languages

- How to improve your Internet conversations

- Hyphens and Dashes—The Long and the Short of It

- Hypothetically Speaking: The English Subjunctive

- In future or in the future: What’s the difference?

- Introduction to macros for language professionals

- Irish Terminology Planning

- Is dictation outmoded?

- It’s a Long Way from Tickle Bay to Success

- "It’s very fun" may no longer be very funny

- Jurilinguistic Management in Canada

- Latin American Idiomatic Expressions

- Less is More: Eliminating on a… basis

- "literacy" and "information literacy"

- Machine translation in a nutshell

- Mankind’s Mother Tongue in the 24th Century

- More on abbreviations

- More Questions from the Inbox

- My quest for information in 2010

- National languages and the acquisition of expertise in technical translation

- Neologisms in dictionaries

- Neologisms then and now

- New questions from the inbox

- New words and novelties

- Old Church Slavonic: It Reads Like a Novel… Almost!

- Online and Offline: To Hyphenate or Not

- Open letter to young language professionals

- Pan-African Glossary on Women and Development

- Parallelism: Writing with Repetition and Rhythm

- Passive Voice: Always Bad?

- Personification of Institutions

- Plain Language: Breaking Down the Literacy Barrier

- Plain Language: Creating Readable Documents

- Plain Language: Evaluating Document Usability

- Plain Language: Making Your Message Intelligible

- Podcasting and Parkour: A Look at 2005

- Portmanteau words

- Prepositional usage with disagree

- Pronoun Management 101

- Pronouns: Form Is Everything

- Publishing in the digital era and expressions in the news

- Punctuation Myths

- Punctuation Pointers: Colons and Semicolons

- Putting It (Even More) Plainly

- Putting It Plainly

- Quasquicentennial

- Questions from the Inbox

- Realistic dreams of a language professional

- Résumés: Up Close and Personal

- Some Thoughts on the Translation of "Volet" into English

- Standing Order 21—We go in hopeful and come out thankful

- Style Myths

- Technical Accuracy Checks of Translation

- That and Which: Which is Which?

- The alchemy of words: Transforming “Le vaisseau d’or” into “The Ship of Gold”

- The Auxiliary Verbs "Must", "Need" and "Dare"

- The case of the disappearing colon: Death by bullets

- The Classification of Bills in the House of Commons

- The Deep Web

- The Diversity of the Abbreviated Form

- The Elusive Dangling Modifier

- The good ship Update

- The Grammar of Numbers

- The How-Tos of Who and Whom

- The human–machine duo: Productive…and positive?

- The Japanese Language: A Victim’s Impressions

- The Language of Shakespeare

- The Language That Wouldn’t Die

- The Other Germanic Threat That French Staved Off

- The People Versus Persons

- There May Be a Hypothec in Your Future!

- The secrets of syntax (Part 1)

- The secrets of syntax (Part 2)

- The SVP Service: A brief history

- The Translation of Hidden Quotations

- The ups and downs of capitalization

- The ups and downs of online collaborative translation

- The Use of the Hyphen in Compound Modifiers

- Through the Lens of History: Colourful personalities, perks and brilliant comebacks

- Through the Lens of History: French: The working language in the West

- Through the Lens of History: Historic, fateful or comical translation errors

- Through the Lens of History: Jean L’Heureux: Interpreter, false priest and Robin Hood

- Through the Lens of History: John Tanner, a white Indian between a rock and a hard place (I)

- Through the Lens of History: John Tanner, a white Indian between a rock and a hard place (II)

- Through the Lens of History: Joseph de Maistre or Alexander Pushkin? The confusion caused by Babel

- Through the Lens of History: Scheming Acadians and translators "dealt a blow to the head by fate"

- Through the Lens of History: Translating dominion as puissance: A case of absurd self-flattery?

- To Be or Not To Be: Maintaining Sentence Unity

- To Drop or Not to Drop Parentheses in Telephone Numbers

- Training Interpreters for La Relève-Part I

- Training Interpreters for La Relève-Part II

- Training Interpreters for La Relève-Part III

- Translating Arabic Names

- Translating the World: Out of Africa

- Translating the World: Uncharted waters

- Translating tweets

- Translation and Bullfighting

- Translation memories and machine translation

- Translators and ad hoc terminology research in the 21st century

- TRENDS

Free Public Domain Software - Trends

This Ordeal has Gone on Long Enough

(Free the data! Free the data! Free the data!) - Understanding Poorly Written Source Texts

- Understanding search engines

- Usage Myths

- Usage Update (Part 1): Verbifying

- Usage Update (Part 2): Deplorable or Acceptable?

- Using headings to improve visual readability

- Voice recognition for language professionals

- Voicewriting

- Voluntary Simplicity in Translation

- Web Addresses: Include http:// and www.?

- WeBiText to the rescue

- Well-Hyphenated Compound Adjectives

- Well-kept translation memory secrets

- What does "Organic" Actually Mean?

- What is a wiki?

- What’s hot

- What’s New?

- Why Do Minutes Count?

- Words First: An Evolving Terminology Relating to Aboriginal Peoples in Canada

- Words from the West

- Wordsleuth (2000, vol. 33, 2)

- Wordsleuth (2000, vol. 33, 4)

- Wordsleuth (2001, vol. 34, 3): The Kumbh Mela

- Wordsleuth (2001, vol. 34, 4): Rip, Mix, Burn?

- Wordsleuth (2002, vol. 35, 1): Too Many Words: Redundancies and Pleonasms

- Wordsleuth (2002, vol. 35, 2): Never Say Never to an Oxymoron

- Wordsleuth (2002, vol. 35, 3): Redundancies—Again

- Wordsleuth (2002, vol. 35, 4): Quiz on Prepositional Usage

- Wordsleuth (2003, vol. 36, 2): A War of Words

- Wordsleuth (2003, vol. 36, 3): Absolute Adjectives—Not So Absolute After All

- Wordsleuth (2004, vol. 1, 1): Of Bangbellies and Banquet Burgers: Updating the Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Wordsleuth (2004, vol. 1, 2): Canadian English: A Real Mouthful

- Wordsleuth (2004, vol. 37, 1): LET’S PARTY!

- Wordsleuth (2004, vol. 37, 2): Here’s to Your Health!

- Wordsleuth (2005, vol. 2, 1): Would a Camrosian by any other name smell as sweet?

- Wordsleuth (2005, vol. 2, 2): 2004 - A YEAR IN WORDS

- Wordsleuth (2005, vol. 2, 3): The Words of Our Lives

- Wordsleuth (2006, vol. 3, 2): Brand Awareness

- Wordsleuth (2006, vol. 3, 3): Test Your Knowledge of Canadiana!

- Wordsleuth (2006, vol. 3, 4): The Dictionary: Disapproving Schoolmarm or Accurate Record?

- Wordsleuth (2007, vol. 4, 1): When the Eye-Gazing Party Ends in a Bump

- Wordsleuth (2007, vol. 4, 2): Rule Britannia

- Wordsleuth (2007, vol. 4, 3): Games Canadians Play

- Wordsleuth (2007, vol. 4, 4): Loyalists to Loonies: A Very Short History of Canadian English

- Wordsleuth (2008, vol. 5, 1): Status quo

- Wordsleuth (2008, vol. 5, 2): Ptoing the Line for a Small Phoe

- Wordsleuth (2008, vol. 5, 3): Test Your Spelling!

- Wordsleuth (2008, vol. 5, 4): All in the Same Boat

- Words Matter: Going Solar

- Words Matter: In the aftermath of Copenhagen

- Words Matter: Translating IT metaphors is not always easy

- Words on the street (Part 1)

- Words on the street (Part 2)

Divulgation proactive

Avis important

La présente version de l'outil Favourite Articles a été archivée et ne sera plus mise à jour jusqu'à son retrait définitif.

Veuillez consulter la version remaniée de l'outil Favourite Articles pour obtenir notre contenu le plus à jour, et n'oubliez pas de modifier vos favoris!

La zone de recherche et les fonctionnalités

Through the Lens of History: Jean L’Heureux: Interpreter, false priest and Robin Hood

Of all the interpreters who roamed Western Canada during the 19th century, Jean L’Heureux was without a doubt the most eccentric. This unusual character who had been refused entry into the priesthood lived for many years among the Blackfoot as a friend and defender of this people. Despite the generous assistance he repeatedly lent to Catholic missionaries and his adopted people, as well as to fur traders and civil authorities, he remained all his life a suspect fringe element of society.

Born in Saint-Hyacinthe sometime between 1825 and 1831, he excelled in the classical education he received, going on to pursue theological training to become a priest. By the end of his first year, however, he was expelled from the major seminary “for serious misconduct.” Thus began his adventurous life as a roving imposter.

False priest

In the mid–1850s, L’Heureux travelled around the gold fields region of Montana. At the Jesuit mission, he passed himself off as a secular priest, obtained a cassock under the pretext that he had lost his own, and set about preaching and performing baptisms and marriages. The Jesuits eventually learnt that he had never been ordained as a priest and discovered with dismay, upon catching him in the act of sodomy, that he was homosexual.

Denounced as a false priest, a sodomite and a fraud, L’Heureux was expelled from the mission. He found refuge among the Blackfoot, who were more inclined to accept him, as Amerindians did not condemn homosexuality. This society was tolerant of berdaches, a fact attested to by the trader Jean-Baptiste Trudeau (1748ââ¬âœ1827), using contemporary vocabulary marked by the prejudices of his time, in his account of his voyage along the upper Missouri River, Voyage sur le Haut-Missouri : 1794-1796:

[Translation] Among all the savage peoples of this continent, there are men who wear women’s dress, who never take part in war or the hunt, who do women’s work, and who make use of both sexes. I could not truthfully tell you what has caused these hermaphrodite-like men to assume this condition, whether it be due to some fanciful idea or an abominable, disturbed passion, as these barbarians have an unfortunate penchant for sodomy.1

From Montana, L’Heureux accompanied a band of Blackfoot to Alberta, where Oblates had been present since 1845. His travels brought him north of Edmonton to the St. Albert mission, led by Father Albert Lacombe (1827ââ¬âœ1916), who hired him as an assistant and interpreter. Hoping to join the community of Oblates, L’Heureux pretended to have changed his ways, but he did not fully convince the fathers, who remained suspicious and sought to neutralize his influence.

The false priest was unrelenting in his evangelization work, “defiling our sacred religion,” deplored Father Lacombe, who would nevertheless remain L’Heureux’s protector until his death, no doubt because the interpreter saved his life during a deadly smallpox epidemic. The deception carried out by this imposter “who preaches and hears confessions” was the cause of great annoyance to the missionaries, all the more so because L’Heureux easily gained the trust of the Aboriginal peoples, whose way of life he shared on a daily basis. The influence he wielded over them must, to some extent, have led to the latent hostility that some of the Oblates felt toward him.

L’Heureux taught the Blackfoot that their traditional beliefs were not incompatible with his own, the only difference being that the Christian God was composed of three persons in one. Finding this idea exceptionally funny, the Amerindians gave L’Heureux the name neokiskaetapiw, meaning “Three Persons.”

Treaty negotiator

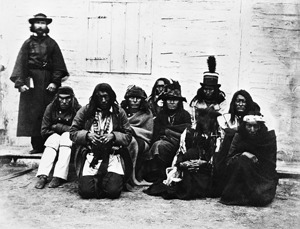

Jean L’Heureux played a major part leading up to and during the Treaty No. 7 negotiations. The territory covered by this treaty was approximately 91,000 square kilometres in southern Alberta. It was inhabited by Blackfoot, Blood, Sarcee, Stoney and Peigan Indians. The Crown coveted this land with a view to opening it up for colonization and any other possible use. It also planned to create reserves by allotting two square kilometres per family of five. The Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories, David Laird, and the Commissioner of the North West Mounted Police,* Lieutenant Colonel James F. Macleod, were charged with conducting the negotiations that took place on September 22, 1877.

Laird wished to engage L’Heureux as interpreter, but L’Heureux advised him that he had already agreed to replace Blackfoot head chief Crowfoot’s interpreter, who was ill, and to be of service to the other chiefs who had requested his assistance.

Enjoying the trust of the Amerindians, L’Heureux was their official spokesperson during the negotiations with the government representatives. He provided the emissaries with valuable information: a map of Blackfoot territory, a census of the various peoples and a list of the head chiefs, main families and various clans. During the negotiations, the interpreter explained the terms of the treaty to the Blackfoot delegates and provided them with advice. An observer commented that L’Heureux “stood unswervingly with the Indians as an Indian.”2

The Blackfoot Confederacy was composed of peoples who spoke different dialects, which necessitated the participation of other interpreters, such as Jerry Potts3 and James Bird Jr., both Metis, as well as Father Constantine Scollen.

Since the interpreters played an active part in the negotiations, it was only normal that their names should appear at the bottom of the treaty as advisers, interpreters and witnesses. L’Heureux inscribed the names of the Blackfoot chiefs on the official document, validated each of their marks and signed the treaty as a witness. It was through L’Heureux that the chiefs thanked the representatives of the Government of Canada.

Robin Hood

Once the treaty had been concluded, Jean L’Heureux chose to live with the Blackfoot and continued to accompany missionaries on their visits to Indian camps. A cultured man of deeply held humanist beliefs, L’Heureux wrote ethnological notes on Blackfoot mores, customs and handmade goods in order to increase awareness of them.

The famines that periodically struck his adopted people following the extinction of the buffalo were of great concern to L’Heureux. In some extreme instances that L’Heureux witnessed, the Indians were reduced to eating ground squirrels, mice, snakes and even animal carcasses half devoured by wolves. To help them, the interpreter petitioned the civil authorities or the mounted police for provisions. He even resorted to stealing horses and livestock, which he then distributed to the most destitute. He felt deep compassion for his hosts in their suffering.

This hardship brought him into contact with Louis Riel (1844ââ¬âœ1885). In the winter of 1879, a famine forced the Blackfoot of Alberta to migrate to an area with more game: Montana. Riel visited them there and, counting on their precarious situation, suggested that they join the Metis in an invasion of the northwest with a view to making it an Amerindian and Metis state. L’Heureux considered it his duty to foil this plot and alerted the Canadian and American authorities. Riel tried again the following autumn, but once again the interpreter intervened and managed to convince the Indians that plotting with Riel and the Metis carried serious risks. He urged them to return to Alberta and to turn a deaf ear to any talk of an uprising.

Official interpreter

In 1881, L’Heureux’s reports on Riel’s seditious activities in Montana earned him the position of interpreter with the Department of Indian Affairs.** He became in a sense the trusted adviser of the Canadian authorities on Blackfoot affairs, acting more or less as an informant.

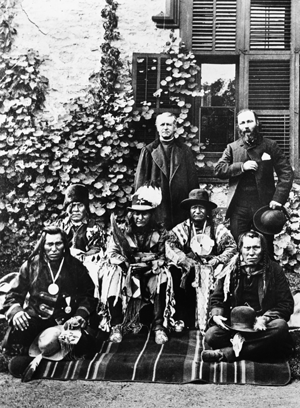

The federal government again showed its appreciation for his work in 1886 by choosing him to travel to Brantford, Ontario, for the inauguration of the statue of Mohawk chief Joseph Brant.*** Also invited to this ceremony were the Amerindian chiefs who abstained from supporting Riel during the rebellion of 1885. L’Heureux was their interpreter and assisted Father Lacombe, who joined them. During the official reception in Ottawa organized by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald in honour of the visitors, the attendees had an opportunity to appreciate Crowfoot’s considerable speaking skills. The head chief’s exceptionally eloquent address was interpreted into English with the same verve by Jean L’Heureux.

In April 1888, L’Heureux was re–engaged as an interpreter through an order-in-council that increased his salary to $600 a year. On top of this generous compensation he received the food rations usually given to officials of the Department of Indian Affairs.4

Missionary assistant

Jean L’Heureux’s relationship with the Oblates was always ambivalent and marked by suspicion. Some of the missionaries viewed him as a “fiend,” others as a nonconformist philanthropist. Not once, however, did they deprive themselves of his assistance. “Of all the services that L’Heureux rendered to the missionary Oblates, the greatest was his recruitment for St. Joseph’s Industrial School, located in Dunbow, southwest of Calgary.”5 The number of ruses and gifts that it must have taken for the interpreter to convince young boys to enrol in the school, and especially to persevere in their studies, was no doubt considerable indeed.

His recruitment work bothered the Protestant ministers, who saw itââ¬ânot without reasonââ¬âas a form of favouritism toward the Catholic Church. As a federal office holder, L’Heureux was expected to exercise a certain degree of impartiality. It should be noted that he opened his home as a boarding house to preschool students whom he was preparing for admission to St. Joseph’s. This continued until an Anglican minister accused him of “practicing immorality of a most beastly type”6 with his young boarders. That was all it took for L’Heureux to lose his employment as an interpreter. No investigation was ever conducted to confirm the allegations, but there was a strong presumption of guilt, given the accused’s past.

Wretched final years

Relieved of his duties in 1891, L’Heureux lived in utter destitution, seeking shelter in the homes of charitable people. Unfortunately, his demands, obsessions and eccentricities quickly became unbearable, and he ended up at the hermitage of his benefactor, Father Lacombe.**** Born, so it seems, for a life of roving, he did not stay there long. He set off again with his bundle of belongings, this time for the foothills of the Rockies, where he lived sometimes as a recluse, sometimes among the Metis. Poor and crippled, he survived on the rations of beef and flour that the government granted him for “services rendered.”

In 1912, L’Heureux had to be placed more or less by force in the home run by Father Lacombe in Midnapore (today a suburb of Calgary). He still wore the cassock and the clerical collar and insisted on being called “Reverend.” It was there that he died in 1919, having almost reached the age of 90. The Oblates have always exercised the greatest discretion as to the contribution made by this “lay missionary” to their proselytizing work in the West. They have reportedly even destroyed the manuscript of his memoirs.

Extraordinary interpreter

Throughout his life, Jean L’Heureux rarely enjoyed unanimous support, even though, thanks to his gift for languages, his undeniable talent as an interpreter and his understanding of the Indian mentality, he earned the trust of Amerindians, religious figures, fur traders and government authorities alike. Each of these groups had, at one time or another, valid grounds to condemn his behaviour. He was called a hypocrite, an imposter, a liar, a thief, a false priest and a troubled soul.

Although reviled by society, this errant Canadian managed to render invaluable services to those around him. The high regard that his large Amerindian family had for him definitely facilitated the Treaty No. 7 negotiationsââ¬âseveral contemporary accounts attest to thisââ¬âand it is not unreasonable to think that thanks, at least in part, to his pacifism, the bloodbath that would have resulted from a Blackfoot uprising in alliance with Louis Riel’s Metis was averted.

The priests made extensive use of his services as a guide, a recruiter and, when they went to administer the sacraments, an interpreter. Bishop Vital Grandin, who actually excommunicated L’Heureux, the pederast, did not have any scruples about suspending the punishment whenever the missionaries required L’Heureux’s services.7 The excommunications were followed by periods of opportunistic “rehabilitation.”

Is this surreal situation not emblematic of the entire life of interpreter Jean L’Heureux, whose tormented existence was marked alternately by acceptance and ostracism?

I would like to thank Alain Otis for the comments and additional information he provided.

Remarks

- * The North West Mounted Police was founded in 1873 by John A. Macdonald. It became “royal” in 1904 and took the name Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1920, following its merger with the Dominion Police, created for the protection of parliamentarians.

- ** The Department of Indian Affairs was created in 1880. Its French name, Département des Affaires des Sauvages, was changed to Département des Affaires indiennes in 1920.

- *** Another statue of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) stands in Confederation Square, Ottawa. The capital’s National Gallery also has a painting, dated 1776, of the famous Mohawk chief, by the English painter George Romney.

- **** St. Michael’s Hermitage was built in 1890 in Pincher Creek, Alberta. In 1908, Father Lacombe founded a home in Midnapore for orphans, the elderly and people with disabilities.

Notes

- 1 Jean-Baptiste Trudeau, Voyage sur le Haut-Missouri : 1794-1796, Septentrion, 2006, p. 189.

- 2 Cited in Hugh A. Dempsey, “Jean L’Heureux,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

- 3 See my profile of “Jerry Potts : guide, interprète et diplomate” in Circuit, No. 111, 2011, pp. 30ââ¬âœ31.

- 4 “Appointment of J. L’Heureux, as interpreter for Black Foot Indians of Alberta, 1888/04/21,” RG 2, Privy Council Office, Series A-1-a, vol. 520, Reel C-3393, No. 974.

- 5 Raymond J.-A. Huel, “Jean L’Heureux : Canadien errant et prétendu missionnaire auprès des Pieds-Noirs,” in G. Allaire, P. Dubé and G. Morcos (eds.), Après dix ans… : bilan et prospective, Institut de recherche de la Faculté Saint-Jean, 1992, pp. 217ââ¬âœ218.

- 6 Reverend J. W. Tims, cited in Raymond J.-A. Huel, Proclaiming the Gospel to the Indians and the Métis, University of Alberta Press, 1996, p. 131.

- 7 Raymond J.-A. Huel, “Jean L’Heureux : …,” pp. 221ââ¬âœ222.

© Services publics et Approvisionnement Canada, 2024

TERMIUM Plus®, la banque de données terminologiques et linguistiques du gouvernement du Canada

Outils d'aide à la rédaction – Favourite Articles

Un produit du Bureau de la traduction