Common menu bar links

Institutional Links

-

Translation Bureau

Language Portal of Canada

-

TERMIUM Plus®

-

Authors

- + Auverana, Iliana

- + Barber, Katherine

- + Blais, François

- + Boileau, Monique

- + Bucens, Vic

- + Cloutier, Yvan

- + Cole, Wayne

- + Collier, Linda P.

- + Collishaw, Barbara

- + Cormier, Chantal

- - Delisle, Jean

- Baudelaire translated in prison by a translation professor

- Fifty Years of Parliamentary Interpretation

- The good ship Update

- Through the Lens of History: Colourful personalities, perks and brilliant comebacks

- Through the Lens of History: French: The working language in the West

- Through the Lens of History: Historic, fateful or comical translation errors

- Through the Lens of History: Jean L’Heureux: Interpreter, false priest and Robin Hood

- Through the Lens of History: John Tanner, a white Indian between a rock and a hard place (I)

- Through the Lens of History: John Tanner, a white Indian between a rock and a hard place (II)

- Through the Lens of History: Joseph de Maistre or Alexander Pushkin? The confusion caused by Babel

- Through the Lens of History: Scheming Acadians and translators "dealt a blow to the head by fate"

- Through the Lens of History: Translating dominion as puissance: A case of absurd self-flattery?

- Voicewriting

- + Doumbia, Bréhima

- + Ethier, Sheila

- + Fitzgerald, Heather

- + Gariépy, Julie L.

- + Gawn, Peter

- + Ghearáin, Helena Ní

- + Guyon, André

- + Harries, Emma

- + Hug, Christine

- + Joe, Gregg

- + Jope, James

- + Lacroix, Kim

- + Laforge, Marc

- + Landry, Alain

- + Lapointe, Lucie

- + Lawrence, C.A.

- + Leighton, Heather

- + Lemieux, Claude

- + Leroux, Paul

- + Matsune, Heather

- + McClintock, Barbara

- + McNamer, Patrick

- + Mossop, Brian

- + Oslund, Richard

- + Ouimet, Nicole

- + Peck, Frances

- + Pontisso, Robert

- + Racicot, André

- + Roberts, David

- + Rodríguez, Nadia

- + Ross, Sheila M.

- + Roumer, Camilo

- + Samson, Emmanuelle

- + Sanders, Sheila

- + Schnell, Bettina

- + Senécal, André

- + Shatalov, Dmitry

- + Siemienska-Vachali, Maja

- + Sitarski, Mary

- + Skeete, Charles

- + Taravella, AnneMarie

- + Tautu, Doris

- + Urdininea, Frances

- + Vittecoq, Fanny

- + Wellington, Me Louise Maguire

Proactive Disclosure

Important notice

This version of Favourite Articles has been archived and won't be updated before it is permanently deleted.

Please consult the revamped version of Favourite Articles for the most up-to-date content, and don't forget to update your bookmarks!

Search and Functionalities Area

Through the Lens of History: French: The working language in the West

The War of the Conquest came to an end through three treaties: the Articles of Capitulation of Québec (1759), the Articles of Capitulation of Montréal (1760) and the Treaty of Paris (1763). These treaties guaranteed all Canadians* free possession of their goods, freedom of commerce, freedom to practise their religion, Catholicism, and the right of return to France within 18 months. However, these treaties did not contain any provisions regarding the French language. How did this impact the language of the fur trade?

The change of allegiance imposed upon Canadians by the Conquest did not deter them from the business in which they excelled—not by a long shot. The amnesty that the authorities in New France granted in 1681 to the coureurs des bois, independent woodsmen who engaged in the fur trade without a permit, had given rise to a new profession, that of voyageur,** and many young men were subsequently employed by Montréal merchants in possession of a trading permit.

A skilled and indispensable workforce

After the Conquest, the number of voyageurs jumped, mainly owing to the creation in 1783 of the North West Company (NWC), a fierce competitor of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), founded in London in 1670, and the American Fur Company (AFC), founded by J. J. Astor, which was in operation from 1808 to 1842. The expansion of the fur trade required the recruitment of a large workforce. Although the new employers were English, the working language would remain French.

In Making the Voyageur World, Carolyn Podruchny estimates the number of voyageurs at 500 in 1784, 1,500 in 1802 and 3,000 in 1821 at the height of the fur trade.1 In Contacts des langues et identités culturelles, Robert Vézina notes that the experience French Canadians acquired in the fur trade in Aboriginal territory, their knowledge of Aboriginal languages, their ability to handle canoes and their adaptability to the Aboriginal lifestyle made them indispensable.2 As noted by Janet Lecompte in French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in the American West, “the ratio of ‘Frenchmen’ to Americans in the fur trade of the United States was not one to four but four to one.”3

Although Canadians dominated the industry through their sheer numbers, they nevertheless occupied the lower ranks of the workforce. The highest positions were held by the English, Scottish and Irish. The shareholders (NWC) or associates (HBC), who held the executive positions, were referred to as bourgeois. Meanwhile, the Canadians were the voyageurs, guides, trappers, dealers, messengers and cooks. For the most part illiterate, they could hardly be promoted to the position of clerk or trading post head. The subordinate roles were therefore mainly assumed by French-speaking labourers.

Within this structure, interpreters formed a distinct class. Occupying the middle ranks between the hired labourers and the bourgeois, they constituted a sort of aristocracy, enjoying special privileges and higher pay than the other employees.

A like-minded community

The Great Lakes region, prohibited to English merchants prior to 1760, subsequently opened up to all those who had the courage to venture there. It would have been unrealistic to ban Canadians and suddenly replace them with inexperienced English traders who had no knowledge of Aboriginal languages.

Canadian traders had forged strong ties of friendship with the Amerindians. Biologist Walter Sheppe makes the following observations in the preface to his publication of the journal Alexander Mackenzie (1764–1820) wrote about his voyage to the Pacific:

…the fur traders lived intimately with the Indians, adopted many of their ways, and took Indian wives. In so doing they became the greatest masters of the wilderness that the continent has ever seen. Their friendship with the Indians permitted them to travel unharmed through regions where other men would not have dared to go.4

For these adventurers, the fur trade was not just a livelihood; it was a way of life.

Indeed, there was a real connection between the Amerindians and the Canadians. Alexander Henry (1739–1824), one of the first Englishmen to try his luck in the fur trade following the Conquest, pointed out that the Canadians’ knowledge, hardiness and skill meant that they were the only men willing and able to go into the fur trade, thus earning for themselves and their employers a monopoly of the trade.5

This was so true that during his first voyage between Montréal and Michilimackinac, in 1761, Henry, on the advice of his guide Étienne-Charles Campion, concealed the fact that he was English, disguising himself as a Canadian voyageur to avoid being massacred by Amerindians.

The Canadians, these people of the land, dispersed throughout the territory, all the way to Illinois. They also engaged in exploration beyond the Great Lakes, spreading out westward until they reached the shores of the Pacific. Ever since La Vérendrye (1685–1749) and his sons, the Canadians had had a sort of pre-emptive right.6 Hundreds of Canadians, scattered across the West, lived among the Amerindians. From these daily contacts, the Metis race emerged.

Impact of the French language

The numerical superiority of Francophones in the fur trade meant that it was beneficial for Anglophones to learn French. Knowledge of French was even one of the qualification criteria for those who held positions requiring them to communicate with the traders. An Englishman in charge of a trading post could go a whole year without having anyone to speak with in English.7

It is well known that French has endured in many place names out West, including south of the border. Journals and accounts of voyages written by various English traders are sprinkled with French expressions, testifying to the fact that the traders were surrounded by Canadians on a daily basis. For instance, notes written by John McLean (1799–1890), who incidentally had learnt French from a priest from Yamaska, include such expressions as compagnons de voyage, casseaux, voie de fait, politesse, partout, débris, solitaire, faux pas and au bout du compte.8

The journal that John McDonnell (1768–1850) kept is also peppered with French expressions, rendered in italics in the English text. In his memoirs, Peter Pond (1739–1807), who knew French before becoming a trader, gently makes fun of his predecessor, Jonathan Carver, for travelling across Aboriginal lands without understanding French or Aboriginal languages.9 Very few Canadians learnt English, whereas the NWC bourgeois, their clerks and, following their example, most English businessmen did learn French.10

The language of the voyageurs and traders

The language of the fur trade had its own vocabulary. Such common expressions as voyageur, Pays d’en haut, bourgeois, engagé, brigade, mariage à la façon du pays*** and ceinture fléchée were in use, as were expressions designating realities unique to the fur trade.

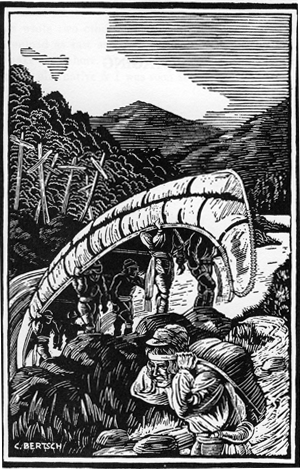

For instance, there was the canot de maître (a ten-metre-long canoe), the canot du nord (a six-metre-long canoe) and the canot bâtard (a canoe under six metres long). Depending on his position in the canoe, a paddler was either a devant, a milieu or a bout. When wintering somewhere, the voyageurs would be on an hivernage. Their work could involve demicharges (half loads) or décharges (unloadings) during the portages. An homme libre (freeman) or a traiteur (trader) could be en dérouine, in other words, off trading in Aboriginal territory far from the trading post, hence the expression courir en dérouine (to trade in Aboriginal territory). The songs the voyageurs sang—such as the chansons à la rame, chansons à l’aviron and chansons de canot à lège—corresponded to the type of canoe used.

The new, less hardy voyageurs from Montréal who did not go farther than Grand-Portage, at the western end of Lake Superior near present-day Thunder Bay, and who, ill-accustomed to pemmican or sagamité (wheat-and-corn-based gruel), sorely missed their mother’s cooking, especially the bread and lard, were referred to with disdain as mangeurs de lard (pork eaters). Pemmican is made by drying buffalo meat in the sun, then grinding it with melted fat until it forms a thick paste, which is quite tasteless, but will not go off for months.

Aller en parole is a nice expression that means to go on a diplomatic or trading mission to negotiate an agreement. The expression appears in the journal kept by trader Jean-Baptiste Trudeau (1748–1827) about his voyage: [translation] “When I was en parole, during the summer of 1795, among the Cheyenne nation, where I lived and spoke with several chiefs….”11

Cassettes (small cases) were used to transport small personal effects, such as medicines, knives and forks. A taureau was a solid buffalo-hide bag capable of holding up to 40 kg of pemmican, a word with which it became synonymous. A taureau was distinguished from a paqueton, a bundle of beaver hides.

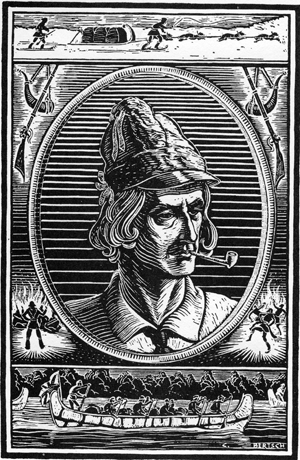

Another expression unique to the voyageurs is faire une pipe.**** The voyageurs paddled 15 to 18 hours a day while remaining in good spirits. Every four or five kilometres, they took a break to relax and smoke a pipe. The distance covered between stops ended up being called a pipe. Incidentally, voyageurs always had a pipe with them and are generally depicted with one.

The currency used out West, the plue, was equivalent in value to one beaver pelt and therefore called “made beaver” (MB) in English. At the HBC counter at Fort Albany in 1733, Native Americans could get any of the following for one MB: 12 needles, 4 lighters, 2 boxes of tobacco, 2 shirts, 2 knives or 1 blanket. The faon is a unit of measurement that corresponds to the quantity a fawn hide can hold; 60 faons of oats, for example, could buy three barrels of rum.

The voyageurs and trappers would dig caches (hiding places), usually all along a waterway. In these approximately two-metre-deep pits, they would store provisions, goods and even canoes for later use. They would then conceal them with dried hides, grass, bark and branches. The word cache is used in many fields today, including computer science.

Since 1968, cache memory has been used to describe buffer storage that holds a copy of instructions and data obtained from the main storage and likely to be required by the processor. Cache memory replaces slave memory dating from 1965. This modern, analog meaning of the word cache stems directly from the vocabulary of the voyageurs. As is the case with the words portage and prairie, it has been assimilated into everyday language.

It would be reasonable to assume that it was largely thanks to the traders, interpreters and missionaries that French has been enriched with so many Amerindian words, such as achigan (bass), babiche (ababich in Mi’kmaq—snowshoe strips), caribou, maskinongé (muskie) and ouaouaron (bullfrog).

From furs to forestry

“French remained the ‘official’ language as long as the fur trade flourished,” states historian Grace L. Nute.12 This assertion is only partially true. Although it is undeniable that French was the language used in the forests, on the waterways and at the trading posts, owing to the Canadians’ dominance in the fur trade, it should be acknowledged that English was the official language of this industry.

The large trading company operators—bourgeois, associates and shareholders—were English, and it was essentially in English that they administered their affairs along Hudson’s Bay (at the Churchill, York Factory and Fort Albany posts), in London, at Grand-Portage (renamed Fort William) and in Montréal, the capital of the fur trade. Very few Francophones were members of Montréal’s prestigious Beaver Club, for example.

It would not be incorrect to say that prior to the Conquest, French was the “official” language of the fur trade, but after 1760 and especially after the founding of the NWC and the AFC, French was the working language. Even though the NWC was sometimes referred to as the “French company,” this was only because a very large majority of its employees were French Canadian, much more than at HBC, which was the “English company.”

In the mid-nineteenth century, the forest industry replaced the fur trade as Canada’s main economic activity, and bit by bit many anglicisms crept into the language of the lumberjacks, as English was more often the language of the operators, suppliers and clients in this new industry. History did not repeat itself.

Illustration sources

Figures 1, 3 and 4—Engravings by Carl W. Bertsch, taken from Grace L. Nute, The Voyageur, 1931, pp. 176, 2 and 34.

Figure 2—Shooting the Rapids (detail) by Frances Anne Hopkins, 1879, Library and Archives Canada, C-002774.

Remarks

- * This term designates French Canadians, who were often referred to simply as “Canadians” or “French” by the English. As for the Canadians, they referred to the English, Scottish and Irish all as “English.”

- ** Voyageur: “[Translation] Labourer hired to transport goods to a trading post in Amerindian territory, returning with pelts, sometimes after spending a winter or longer at the post, or hired to fill various roles (guide, canoer, portager, etc.) during voyages of exploration in Amerindian territory” (Poirier, Claude [ed.] (1998), Dictionnaire historique du français québécois, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, p. 516).

- *** See “John Tanner, a white Indian between a rock and a hard place (I),” Language Update, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Summer 2011), p. 19. The article also appears in Favourite Articles.

- **** Nowadays, faire une pipe is a vulgar expression.

Notes

- 1 Carolyn Podruchny, Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade, University of Toronto Press, 2006, pp. 4-5.

- 2 Robert Vézina, “La dynamique des langues dans la traite des fourrures : 1760-1850,” in D. Latin and C. Poirier (eds), Contacts des langues et identités culturelles. Perspectives lexicographiques, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2000, p. 144.

- 3 Janet Lecompte in LeRoy R. Hafen (ed.), French Fur Traders and Voyageurs in the American West, University of Nebraska Press, 1977, p. 11.

- 4 In Alexander Mackenzie, First Man West: Alexander Mackenzie’s Journal of his Voyage to the Pacific Coast of Canada in 1793 [c. 1801], McGill University, 1962, p. 6.

- 5 Alexander Henry in David A. Armour (ed.), Attack at Michilimackinac 1763, Mackinac Island State Park Commission, 1971, p. 33.

- 6 Marcel Giraud, Le Métis canadien : Son rôle dans l’histoire des provinces de l’Ouest, Institut d’ethnologie, 1945, p. 214.

- 7 Robert Rumilly, La Compagnie du Nord-Ouest : une épopée montréalaise, Fides, 1980, Vol. 1, p. 133.

- 8 John McLean, Notes of a Twenty-Five Years’ Service in the Hudson’s Bay Territory, R. Bentley, 1849.

- 9 Benoît Brouillette, La pénétration du continent américain par les Canadiens français, 1763-1846 : traitants, explorateurs, missionnaires, 2nd ed., Fides, 1979, p. 59.

- 10 Rumilly, Op. cit., p. 152.

- 11 Jean-Baptiste Trudeau, Voyage sur le Haut-Missouri : 1794-1796, text edited and annotated by Fernand Grenier and Nilma Saint-Gelais, Septentrion, 2006, p. 155.

- 12 Grace L. Nute, The Voyageur, Appleton, 1931, p. 5.

© Public Services and Procurement Canada, 2024

TERMIUM Plus®, the Government of Canada's terminology and linguistic data bank

Writing tools – Favourite Articles

A product of the Translation Bureau